The Sakhalin Koreans are descendants of Koreans brought to Sakhalin Island during Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea. Many were forcibly relocated or economically compelled to work in harsh conditions on the island’s fisheries, logging, and coal mines. After Japan’s defeat in World War II, these Koreans were left stateless, caught between the Soviet Union, Japan, and the divided Korean Peninsula.

While some eventually repatriated to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) or South Korea, many remain in Russia to this day, preserving a unique and often overlooked cultural identity that embodies resilience and survival through turbulent times.

Labour under Japanese rule

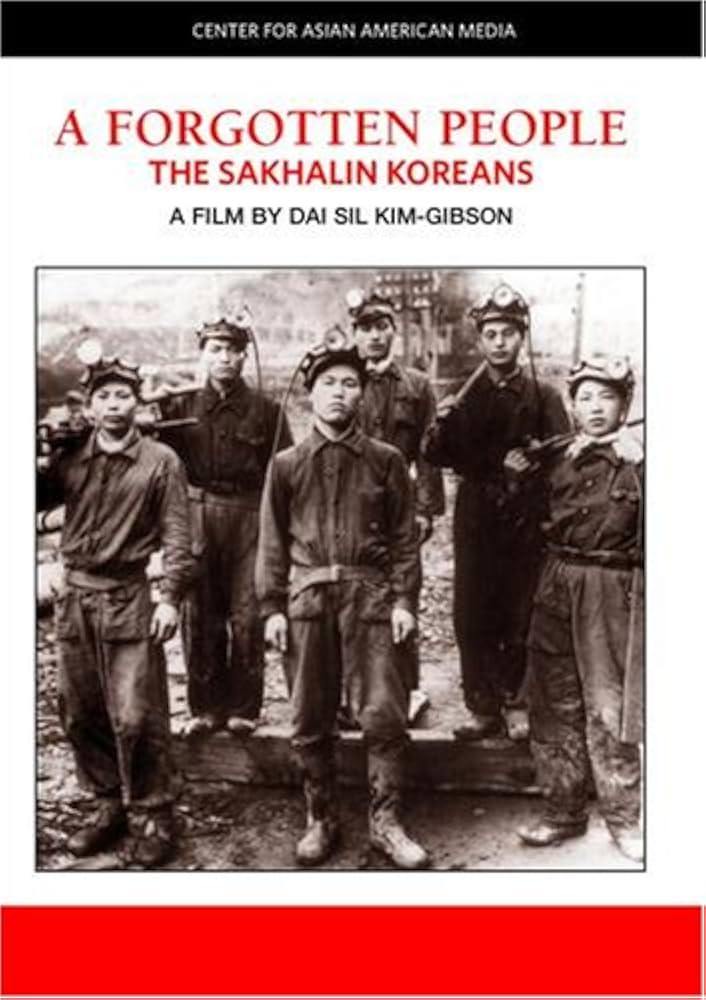

Following Japan’s 1910 annexation of Korea, thousands of Koreans were sent to Sakhalin—then known as Karafuto—to fulfill labour demands in industries vital to Japan’s war efforts. During the Russo-Japanese War, Japan’s control of Sakhalin became strategically important, and Korean labourers formed a significant part of the workforce. These Koreans were employed primarily in fishing, coal mining, and forestry, sectors critical for Japan’s growing empire. Despite their contributions, Koreans on Sakhalin were denied Japanese citizenship, often subjected to brutal working conditions, and lived in segregated communities under strict military and administrative control.

The conditions they endured, ranging from insufficient shelter to meager rations and minimal medical care, left lasting scars on the community. Yet, even in these harsh circumstances, Koreans found ways to preserve their language and cultural practices, passing traditions down to younger generations despite being physically and politically isolated from their homeland.

Abandoned after World War II

The end of World War II brought significant geopolitical upheaval. When Japan surrendered in 1945, Japanese settlers were repatriated en masse. However, the Koreans who had been brought to Sakhalin were largely left behind. Neither Japan nor the newly established South Korean government accepted responsibility for their welfare. The Soviet Union, now in control of Sakhalin, classified them as former colonial subjects and did not permit their repatriation, effectively rendering the Sakhalin Koreans stateless.

Moreover, during Stalin’s reign, many Sakhalin Koreans were forcibly deported to Central Asia as part of broader ethnic cleansing policies aimed at several minority groups, including Crimean Tatars and Volga Germans. This dispersal fractured families and communities, complicating the collective identity of Sakhalin Koreans. Political borders, ideological divides, and Cold War tensions meant many families were separated for decades, unable to reconnect due to restrictions imposed by multiple governments.

Cultural preservation in isolation

Cut off from the Korean Peninsula and isolated by Soviet governance, Sakhalin Koreans managed to preserve traditional dialects, customs, and celebrations. Holidays such as Chuseok and Lunar New Year are still observed, often reflecting cultural expressions closer to early 20th century Korean traditions than those evolving on the peninsula itself. This cultural preservation is a source of pride and identity for the community.

While Sakhalin Koreans’ traditions remained insulated, Korean diaspora communities in other regions developed under very different circumstances. For example, Yanji, located near the border between China and North Korea, has evolved into a vibrant Korean cultural enclave, with its own distinct customs and cuisine. The culinary scene in Yanji highlights the diversity of Korean food culture beyond the peninsula, as documented by street food experts. Such contrasts help illuminate the singular cultural path that Sakhalin Koreans have traversed.

Return migration and challenges

From the 1950s onward, many Sakhalin Koreans sought to reconnect with their ancestral homeland. A significant number relocated to the DPRK, motivated by the hope of reunification and a shared Korean identity. Others moved to South Korea, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, seeking economic opportunities and social integration.

However, the returnees faced significant challenges. In South Korea, differences in dialect, cultural customs, and decades of divergent experience led to discrimination and social marginalization. Many returnees struggled to adapt to a society that viewed them as outsiders despite shared heritage. Similarly, those relocating to the DPRK encountered difficulties adjusting to the highly regimented political and social system, which differed starkly from their lives in the Soviet Union.

These struggles underscore the complex realities of Korean reunification, which remains elusive despite decades of diplomatic efforts and cultural longing. The experiences of the Sakhalin Koreans exemplify how political divisions have lasting human consequences.

Stalin’s legacy and deportations

The deportations ordered by Stalin deeply shaped the Sakhalin Korean community’s history and identity. As part of the Soviet government’s ethnic cleansing strategies, many were uprooted from their homes and sent to remote regions of Central Asia, often facing hostile environments and further marginalization.

The descendants of these deportees today carry layered identities, balancing their Korean cultural heritage with the realities of Soviet exile. Many still maintain Korean language skills, traditional customs, and a collective memory of displacement. These experiences reflect broader patterns of diaspora survival under oppressive regimes.

Geopolitical complexity

Sakhalin Island’s geographic position near the borders of Russia, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula places it at a geopolitical crossroads. This unique location creates a complex social and political environment for the Sakhalin Koreans. The presence of North Korean workers in the area adds further nuance, with intelligence and espionage concerns reported due to the overlapping interests of regional powers.

The intricate relationships between these communities highlight ongoing tensions and the delicate balance required to navigate identity, loyalty, and survival in a region marked by historical conflict and shifting alliances.

Today’s community

Despite decades of hardship and displacement, Sakhalin Koreans maintain a resilient cultural presence in Russia. Community organizations, schools, and religious institutions play central roles in preserving language and traditions. Annual cultural festivals and gatherings serve as important reminders of their shared heritage.

Some Sakhalin Koreans have successfully resettled in South Korea or the DPRK, though social integration remains challenging. Their stories continue to reveal the complex intersections of history, identity, and geopolitics that define the Korean diaspora today.

Click to check out our travel packages.